Algonquian Word-Structure Basics

(Written for the Nisinoon Project; last updated December 31, 2024)

Introduction

This document provides an overview of word structure in Algonquian languages.

Caveat: The view in this document is strongly influenced by my familiarity with some of the Central Algonquian languages (especially Menominee); it may not be quite right for some of the other languages, especially the Plains languages, which are really different. But this should work for most of the languages. I will make updates as I learn more! (Input appreciated!)

Contents

- Lexical Categories (Parts of Speech)

- Derivation vs. Inflection

- Components

- Hyphenation

- Animacy

- Verb Types

- Paired Verb Stems

- Primary vs. Secondary Derivation

- Formatives

- Deverbal Formations

- References

Lexical Categories (Parts of Speech) (back to contents)

The classic way to divide up Algonquian lexical categories at the very highest level is according to whether they inflect or not (see next section for the distinction between Derivation vs. Inflection):

- Do inflect (take endings)

- Verbs

- Nouns

- Do not inflect

- Particles

Sometimes a few other things are included under the “do inflect” heading, e.g., pronouns, negators, etc. Particle is usually a vast category, and some authors subdivide it further, adding, for example, prepositions (see, e.g., Oxford [2007] for discussion of the category particle in Innu-Aimun).

Note that there aren’t any adjectives or adverbs (although some authors do use these labels).

Derivation vs. Inflection (back to contents)

The distinction is a little fuzzy around the edges, but basically:

- Derivation creates stems; derivational morphemes have meaning or function (like making a noun stem into a verb stem)

- Inflection creates words; adds information that doesn’t really change the meaning of the stem; it just provides information like person (e.g. the subject is first person ‘I’, number (singular or plural), etc.

In Algonquian languages you pretty much always have to have inflection on verbs (except in some cases where we might argue that there’s a zero morpheme).

This project is concerned with the derivational morphemes of Algonquian.

Components (back to contents)

The basic derivational morphemes in Algonquian languages are called components, and Nisinoon is a cross-Algonquian dictionary of these components. There are three types, which correspond to where in the stem they appear. These are illustrated in the following template:

| Initial | Medial | Final |

- Initials are also called roots.

- Medials tend to be nominal in character and are optional.

- Finals determine the lexical category (part of speech) of the stem, and sometimes add additional meaning too.

There are (at least!) two ways of looking at the make-up of stems: one view is that a stem can be formed of an initial by itself; an initial and a final; or an initial, a medial, and a final (see, e.g., Goddard 1990). The other view is that initials and finals are obligatory, but sometimes the final is a zero morpheme just carrying lexical category (Cowell and Moss [2008], for example, take this view for verb stems; see also Wolfart [1973]).

Some authors allow for double medials; other authors do not. Authors who want to rule them out will say one of the (apparent) medials is really part of another component. Either way, though, it’s not common.

Finals can just give a word its lexical category (in which case they’re called abstract), or they can have some lexical meaning in addition to providing a lexical category (in which case they’re called concrete). Some authors divide finals into a concrete part and an abstract part (see below, on formatives).

Examples (components in slashes in the third line; this line does not include inflectional morphology):

Menominee

pemētaehkipew

- paemet‑crosswiseinitial

- ‑aehkw‑facemedial

- ‑apesitfinal

‘S/he sits sideways.’

Bloomfield (1975: 208)

SW Ojibwe

ozhaashisagaa

- ozhaash‑slipperyinitial

- ‑sag‑floormedial

- ‑aastatfinal

‘It is a slippery floor.’

Nichols (2015)

Delaware

kwənaskwat

- kwən‑longinitial

- ‑askw‑grassmedial

- ‑atinanfinal

‘It is long grass.’

O’Meara (1990: 250)

Blackfoot

sisáápittakit

- siso‑cutinitial

- ‑ap‑stringlikemedial

- ‑ittakiby.bladefinal

‘shred (the hide) into strips’

Frantz & Genee (2015)

(In these examples, the components are given in their underlying forms, which differ in some cases from the forms as they show up in the actual word.)

Components occur in all lexical categories, not just verbs. But the particles tend to be fairly simple in structure, and the nouns are generally simpler than the verbs. It’s in the verbs that you see the really complex combinations.

Hyphenation (back to contents)

In Nisinoon, our standard for hyphens is:

- Initials: hyphen at right, e.g. siso‑ ‘cut’; Blackfoot

- Medials: hyphen on both sides, e.g. ‑askw‑ ‘grass’; Delaware

- Finals: hyphen at left, e.g. ‑ape ‘sit’; Menominee

However, other authors don’t necessarily follow this. In that case we enter the data their way but convert it to the standard above in the project orthography.

Animacy (back to contents)

Nouns in Algonquian languages can be animate or inanimate.

-

This can correlate with intuitive notions of animacy, i.e. if something is living it should be animate, but if not, it should be inanimate. But this is by no means always the case. It’s just like gender in European languages—there, some nouns might be masculine, some might be feminine, but there’s not necessarily any correlation with the object and sex. (Tables are feminine in Spanish, but masculine in German, for example. Why?) There’s a huge literature on why particular nouns are either animate or inanimate in Algonquian languages; for our purposes we’ll just say it can be arbitrary.

-

In most of the languages the plural is different depending on animacy—e.g. in Menominee, animate plurals have the suffix ‑ak and inanimate plurals have the suffix ‑an (āmōw ‘bee’, āmōwak ‘bees’; mēn ‘blueberry’, mēnan ‘blueberries’).

-

In a few of the languages, e.g. Miami-Illinois (and in the hypothetical proto-language), the singular also has different suffixes depending on animacy.

-

Verbs agree with subjects or objects in animacy; see next section.

Verb Types (back to contents)

Verbs in Algonquian languages are categorized in two ways:

- Transitivity (intransitive just has a subject; transitive has subject and object)

- Animacy (animate or inanimate)

The two intersect like this:

| Subject | Object | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Animate Intransitive | ai | animate | |

| Inanimate Intransitives | ii | inanimate | |

| Transitive Animate | ta | animate | |

| Transitive Inanimate | ti | inanimate |

That is, intransitive verbs are categorized by the animacy of their subjects (and of course they don’t have objects), and transitive verbs are categorized by the animacy of their objects. The abbreviations given for each type are used extensively.

This matters because there are different verb paradigms (sets of endings) for each type. And for our purposes, verb finals will create not just verb stems, but verb stems of a particular type (e.g. a ta verb stem).

Some of the types have subcategories, which are usually numbered—the ai and ti verbs have these, so you’ll see e.g. ai2 or ti1. In some of the languages you’ll see, e.g., ti1a and ti1b.

Paired Verb Stems (back to contents)

Usually, verbs come in pairs—ai and ii, ta and ti. For example, in Menominee:

-

pāpaehcen ‘he, she, it (an.) falls’ (ai)

pāpaehnaen ‘it (inan.) falls’ (ii)

Bloomfield (1975: 200)

-

na͞ewa͞ew ‘s/he sees him, her, it (an.)’ (ta)

na͞emwah ‘s/he sees it (inan.)’ (ti)

Bloomfield (1975: 154)

You can see that they differ, but only a bit. Usually the difference comes in the final, which makes sense, because that’s the component that gives a stem its category.

In some cases you find sets of four, where all four verb types are based on a common initial, e.g. Menominee maehkīhotaew ‘it (inanimate) is painted red’ ii, maehkīhosow ‘it (animate) is painted red’ (ai), maehkīhonaew ‘s/he paints him, her, it (animate) red’ ta, and maehkīhotaw ‘s/he paints it red’ ti.

Primary vs. Secondary Derivation (back to contents)

What was described in the Components section is what is known as primary derivation, where an initial, an optional medial, and a final form a stem. But you can take a stem created this way and add another final to it to create a larger stem—this is called secondary derivation. (Authors use different terms for what I’m calling the “stem” here; some call it an “initial” or a “derived initial”.) These are illustrated below (these templates come from my in-progress Menominee grammar [Macaulay, in prep]):

| Initial | Medial | Final |

|

|

|||||||

Some finals can only be used in primary derivation, some can only be used in secondary derivation, but some can be used in both.

Following are some examples from Menominee:

-

kōhkawaew (ai) ‘it (animate; for example, a wagon or canoe) tips over’

Stem: kōhkawae‑ [initial kōhkā‑ ‘tip over’ + ‑āwa͞e ‘ai final’]

Secondary final: ‑makat ‘ii verb’

New word: kōhkawaemakat ii ‘it tips over’

Bloomfield (1975: 103)

-

cēkataham (ti) ‘he or she sweeps it clear, cleans it with a broom’

Stem: cēkatah‑ [initial cēk‑ ‘near, next to’ (?) + ‑atah ‘by stick’]

Secondary final: ‑ka͞e ‘ai verb; indefinite action’

New word: cēkatahekaew (ai1) ‘he or she sweeps’

Bloomfield (1975: 42)

-

wāqnenam (ti) ‘he or she throws light on it, lights it up’

Stem: wāqnen‑ [initial wāqN‑ ‘light’ + ‑aen ‘by hand’]

Secondary final: ‑kan ‘n; instrument, product, place, etc.’

New word: wāqnenekan (n) ‘lamp, candle’

Bloomfield (1975: 267)

-

sūniyan (n) ‘money’

Stem: sūniyan‑ [initial sōni‑ ‘silver’ + ‑ān ‘n final’ (?)]

Secondary final: ‑ikamekw ‘n; house, building’

New word: sūniyanikamek (n) ‘bank’

Bloomfield (1975: 244) & Sarah Skubitz (4/3/00)

These examples represent the standard kind of secondary derivation, where a final is added to a stem. Very rarely, you’ll find an analysis in which secondary derivation can be added a medial as well as a final (e.g. Drapeau 1980: 317).

Formatives (back to contents)

Traditionally, Algonquianists have recognized another level or layer of derivation, saying that components can themselves be made up of more than one piece. There’s no standard name for this sub-component element; we’ve adopted the word formative for it.

In this project, we believe that what looks like sub-component elements are really historical relics, and should not be treated as synchronically present in a word’s analysis. But it’s important for the database to be true to the sources we get the data from, so if they include formatives in their analysis, we are entering them.

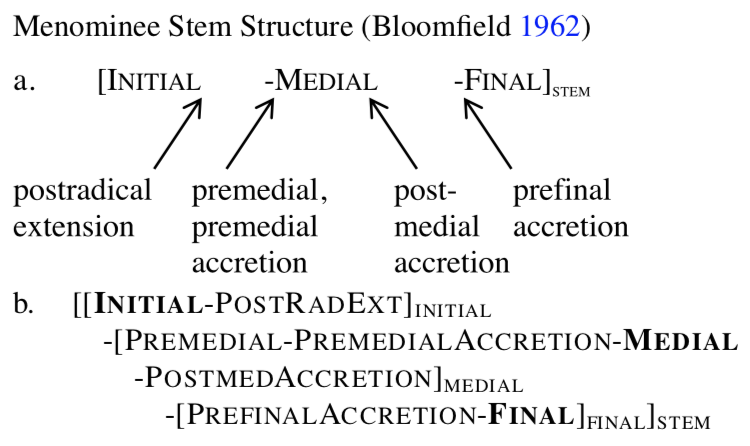

The types of formatives can include:

- Postradical extensions (also called postinitials)

- Premedials

- Premedial accretions

- Postmedials

- Prefinal accretions

This list (examples appear below) comes from Bloomfield’s (1962) grammar of Menominee; other authors may use other terms or include other types. Some of the formative types are claimed to be meaningful; others are just phonological material that attaches to a component (the accretions and extensions).

The example below comes from a paper I coauthored on this topic (Macaulay & Salmons 2017) and shows where each type of formative attaches to the component it goes with.

Examples of formatives (all from Bloomfield’s analysis of Menominee):

-

Postradical extensions

The initial īqsaw‑ ‘to one side’ is found in īqsawekāpowew ‘he, she, it (animate) stands bent to one side’. It shows up with the postradical extension ‑a͞e in īqsawa͞ehkaw ‘he, she, it (animate) moves to one side’.

-

Premedials

This is one of the ways of getting around saying a word can have two medials. Premedials appear as the first “part of a complex medial suffix. Thus, beside ‑qkw‑ ‘eye, face’, there is ‑ānakeqkw‑ ‘eye’, with ‑ānak‑ ‘opening’ as a premedial” (Bloomfield 1962: 381).

-

Premedial accretions

The medial ‑kamy‑ ‘water, liquid’ appears in tahkīkamiw ‘it is cool water’. It appears with a premedial accretion ā‑ in apīsākamiw ‘it is a black liquid’.

-

Postmedials

The medial ‑qsahkwan‑ ‘nose’ appears in wīneqsāhkwan ‘s/he has a dirty nose’ (there’s a final vowel which is deleted so that it looks like there’s no final, but there is). In kesīqsahkwana͞eha͞ew ‘s/he wipes his or her nose for him or her’ the medial has a postmedial ‑a͞e (‑qsahkwana͞e‑).

-

Prefinal accretions

The noun oma͞eqnomenēw ‘Menominee’ can be secondarily derived to oma͞eqnomenēweqnaesew ‘s/he speaks Menominee’ with the final ‑qnaese ‘speak’. But the noun mōhkomān ‘white person’ becomes mōhkomānēweqnaesew ‘s/he speaks English’ with a prefinal accretion ēw‑ added to the final.

For authors who divide finals into two parts, a concrete part and an abstract part (mentioned above), the prefinal corresponds to the concrete part.

The problem we have with the notion of formative has to do with the definition of morpheme. A morpheme is supposed to be the smallest unit of sound and meaning or function. But if components are morphemes, then what are the formatives? Morphemes shouldn’t be made up of smaller parts, especially meaningful parts (like with the premedials). But if the formatives are the morphemes, then what status does the component have? If it’s not a morpheme, what is it?

Following (Macaulay & Salmons 2017), we treat cases in which a component has multiple forms (e.g. one with, one without an accretion) as allomorphs of the same morpheme.

Deverbal Formations (back to contents)

Deverbal in the sense it is used here means “formed from a word” (not formed from a verb).

The traditional Algonquianists also see derivation happening to create morphemes. They very correctly recognize the relationship between full words (or stems or roots) and morphemes, but take it the extra step to say that the morpheme is derived from the word. The problem is, if this is a synchronic operation, where in the grammar could it occur?

For example, Bloomfield believed that a number of finals were derived from stems or words (“deverbal finals”). He cites the word mahka͞esen ‘shoe, moccasin’ and notes that in a word like maeqtekuahkesen ‘wooden shoe’ we find a final of the form ‑ahkaesen ‘shoe’. For him, the fact that they’re similar means the latter is derived from the former—apparently synchronically, although he’s (frustratingly) never specific.

Although we believe that this kind of relationship is purely historical, when an author says that something is deverbal, we make a note of it in the database, and note the source, if they give it.

References (back to contents)

- Bloomfield, Leonard. 1962. The Menomini Language. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Bloomfield, Leonard. 1975. Menominee Lexicon. Ed. Charles F. Hockett. Milwaukee Public Museum Publications in Anthropology and History No. 3.

- Cowell, Andrew and Alonzo Moss Sr. 2008. The Arapaho Language. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Drapeau, Lynn. 1980. Le rôle des racines en morphologie derivationelle. Recherches linguistiques à Montréal 14:313-326.

- Frantz, Don & Inge Genee (eds.). 2015–2020. Blackfoot Dictionary. https://dictionary.blackfoot.atlas-ling.ca.

- Goddard, Ives. 1990. Primary and Secondary Stem Derivation in Algonquian. International Journal of American Linguistics 56(4):449-483.

- Macaulay, Monica. in preparation. Menominee Reference Grammar.

- Macaulay, Monica and Joseph Salmons. 2017. Synchrony and Diachrony in Menominee Derivational Morphology. Morphology 27(2):179-215.

- Nichols, John D. 2015. Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/main-entry/ozhaashisagaa-vii.

- O’Meara, John. 1990. Delaware Stem Morphology. Montreal, Quebec: McGill University Ph.D. dissertation

- Oxford, Will. 2007. Towards a Grammar of Innu-Aimun Particles. M.A. thesis, Department of Linguistics, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Wolfart, H. Christoph. 1973. Plains Cree: A Grammatical Study. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol 63(5):1-90. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.